Sometimes scientists discover answers to questions they weren’t asking. Tramping through the forests of Colorado, ponderosa pines rising with the granite slopes of the mountains, M.J. Riches and her colleagues were asking about the organic compounds trees release when they breathe. Trees have tiny pores on their leaves called stomata, which inhale the surrounding air so that the leaf can extract the carbon dioxide needed for photosynthesis. Then the leaf lets out oxygen and the organic compounds that make a forest smell like a forest. Those were the particles Riches and her collaborators planned to study. Each day they held their instruments to the branches of the pines and measured the chemical make-up of the air around the exhaling needles. But one day, as the Cameron Peak Fire blazed to the north and smoke settled heavy over the valleys, Riches checked her instruments and realized something strange. The increased oxygen and organic compounds that should have been present in the air close to the needles weren’t there. The same readings came back the next day, and the next. The results were clear: the trees weren’t breathing.

I have always been a porous person. Everything bothers me: smells, sounds, gentle teasing, bumper stickers (and people who talk like them), misplaced modifiers, particular shades of yellow. I get sad about trees dying. I get sad about the weather. Like a salamander, I breathe through my skin.

I have tried to not be this way. In my teens I struggled desperately to style myself like the heroines in the fantasy novels I was reading—sarcastic, self-reliant, tough. In my twenties I chased a more monastic discipline: rise early sinner, eat thy apportioned vegetables, read the day’s pages, earn thy bread, run thine mile, now more vegetables, now more labor, now to bed. Sometimes I managed it. But more often some small thing—a sidelong glance from a coworker that seemed heavy with meaning I couldn’t decipher, the potent silence following a text I’d sent to a friend—would upend the day, interrupting the slog from work to treadmill. I’d fidget and shift, seek comfort in television, seek comfort in sleep.

Now as I tip further into my fourth decade, I’m resolved to try again—not to make myself a scorpion wearing her gleaming exoskeleton, nor the army ant marching in step beneath his heavy load. Apparently, I’m not built for such lives. But I think I see another way.

When Riches and her colleagues realized the trees weren’t breathing—weren’t taking in the carbon dioxide essential for photosynthesis—the immediate question was “why.” Was the smoke settling on the pine needles and clogging their pores? She adjusted her experiment. On smoky days over the next two summers, her team brought their instruments out into the forest and took their readings. No respiration. Then they altered the temperature and humidity around particular branches. Trees’ stomata can widen or contract depending on the conditions in the atmosphere. The scientists were curious if they could effectively “defibrillate” the pine’s needles, get them to start breathing again. Within an hour, their instruments picked up normal levels of oxygen and organic compounds. Perhaps, Riches wondered, the trees had evolved to close their stomata in smokey environments, protecting themselves from the ash particles and other harmful gases.

Perhaps, if I can’t be a scorpion, I can be a ponderosa pine.

The writer and researcher Brene Brown has pointed out that we can’t selectively numb our emotions. We can’t shut out sorrow, anger, or anxiety and still expect to feel joy, curiosity, contentment, hope. A tree can keep dangerous smoke particles out of its leaves, but only by holding its breath. We don’t want to suffocate ourselves into cynicism or indifference, especially in a world with so much suffering, and yet we need to protect ourselves. We cannot absorb everything and hope to carry on.

Like the trees, we can react to the air around us. So when a man at church asks if he can give me “some free advice, young lady?” and then lectures me (incorrectly) about how I sing the Mass, I feel something inside me shut tight. “No,” it whispers, “I will not let this in. I will not let this past my defenses.” Or when a student (who I seriously suspect hasn’t read a single word for class) leans over to a friend whispers snidely about the “usefulness” of the course, I stand a little straighter. I will not let this in. I will not let this in. I will not let this in. And then, when I step through my door at the end of the day, or take a walk along the river between classes, or sit in my car waiting one child or the other to clamber in beside me, I released what was clenched, pull a long breath down, down into my belly. The wind shifts and the smoke moves off. I breathe.

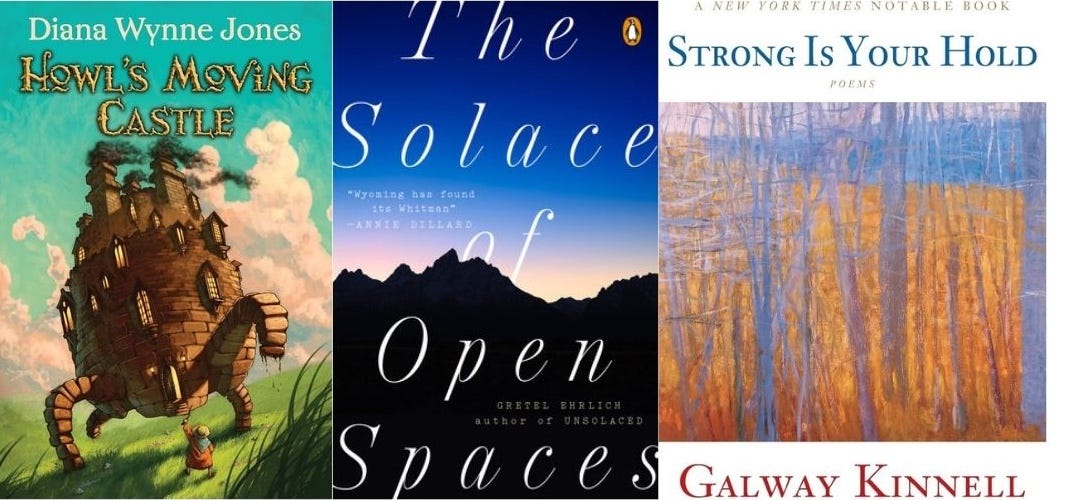

Some books to books to burrow into for comfort and rest as the days get darker:

If you’re looking for a wholesome YA novel that will charm your pants off, read Howl’s Moving Castle by Diana Wynn Jones. And if you recognize the title, yes, this is the book Hayao Miyazaki based his film on. I love the movie so much, I couldn’t image the book being better. But somehow it is. It’s got whimsical magic, delightful characters, and a plot with so many twists and turns, it will leave your head spinning. I know the YA market churns out a lot of poorly written slop these days, but this book is different. Jones studied under J. R. R. Tolkien. She’s a serious writer who writes smart books for young (or not so young) people. I can’t recommend this one enough.

If you want a short read about the brutal beauty of rural Wyoming and the people who live there, read The Solace of Open Spaces by Gretel Ehrlich. After the death of her husband and the utter collapse of life as she knew it, Ehrlich moved west and became a sheep herder on a ranch: spending weeks alone in the mountains with only her flock and the empty sky. The book is as austere and gorgeous, as full of sharp violence and immense peace, as the landscape it describes.

If you want poems that read like a modern Robert Frost, pick up Strong Is Your Hold by Galway Kinnell. Deeply in touch with the landscape of the American northeast, Kinnell’s poems feel like a warm quilt on a cold night. They are plainspoken, tender, and deeply attuned to the world around him. Here’s a good one if you want a teaser trailer.