Sometime in spring, before the buds were on my grape vines or the cardinal had begun her nest in the birch tree, I ordered my stepson a twenty-pound box of un-cracked geodes. He shares my love of mineralogy, the strangeness of chemicals taking fantastical shapes, how bismuth crystalizes into its alien rainbow circuitry, or stibnite forms its slender explosions of gunmetal shards. I thought cracking the geodes would be a fun treat from time to time, an easy scrap of delight on an otherwise time scuttled day.

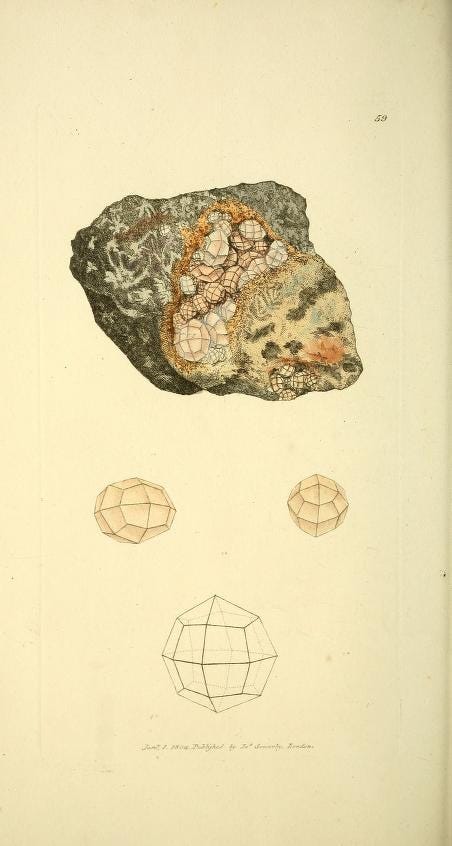

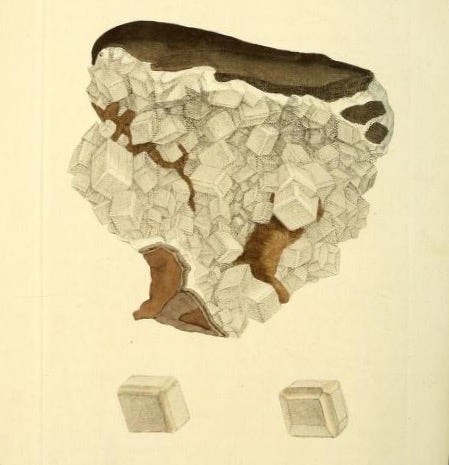

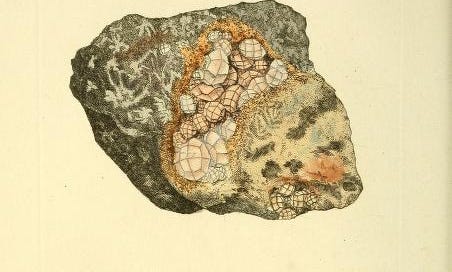

The first few—the smallest of the box—came apart easily. A couple strikes with our big claw hammer and the fragments skittered across the back patio, the bland gray lumps splitting into cups frothing with glittering white crystals. We would sit together on the concrete, comparing different pieces, tilting them this way and that in the light, wondering at surprises these nondescript stones carried inside.

The French theorist and psychoanalyst Anne Dufourmantelle wrote that one of the innovations of Christianity was to create a sacrosanct space between the self and its god, a secret garden that could not be violated by church or state. No one, not even a papal tribunal, could compel a Christian to share what she had whispered in prayer, nor what, if anything, her god had answered. Each person contained an inviolable a place she could retreat to in deepest vulnerability or need.

We live in a world with no such boundaries. Internet culture demands we divulge our private lives as proof of our existence, our happiness, our success. Many trees are falling in our collective forests, and we must make sure someone hears ours. Many thinkers have written about the ways this causes us to surveil ourselves, to constantly position our bodies and thoughts to be “likable” to whatever public. We pose even when there isn’t a camera. Sensor ourselves without realizing the Twitter mob is in our heads. I’m no exception. I catch myself feeling dissatisfied with a vacation unless I’ve captured it in pixels and flattering light.

My question here is slightly different: what has it done to the human psyche to lose the secret garden, to forget we ever valued it to begin with. Dufourmantelle suggests that without our inner gardens, we forget that our personhood exists, glittering and undeniable, independent of all social context, beyond career and family, hobbies and friendships. In the garden, we don’t rely on a reacting public to give our personhood value or meaning. We feel the value of the self as we walk the light-stippled paths of our thoughts. Without that assurance, without that experience of the undeniable reality of the self independent of all external validation, we become fearful, anxious, insecure—which in turn makes us less free. To turn towards our inner garden in the modern world, Dufourmantelle writes, is “the madness of believing against all ‘apparent’ reason that there, behind you, is a reserve of freedom like no other.” When we rediscover this secret space, it becomes a place of retreat where we can flee from the world’s clamoring babble. The self becomes a place of potential where we can contemplate mutiny against the world order in absolute security.

But like all gardens, this inner sanctum needs to be cultivated. We have to spend time there. And if that time is no longer structured by conversation with an almighty god, it needs something else to give it shape.

As my step son and I worked our way up through the geodes they became more and more difficult. We’d sit for hours on the cement of our front walk, passing the hammer back and forth, flinching back when a spark sprung from the stone and the acrid smell of burnt iron filled the air. One came apart to reveal crystals laced with red, iron particles tucked and rusting around the quartz. Another opened to feathered, dove-gray shards that looked soft enough to sleep on.

The largest, about eight inches across, is still sitting in its cardboard box on the back porch. We’ve tried everything. We’ve hit it with every hammer. Dropped it from increasingly ill-advised heights. Hit it against other rocks, other bricks. It sits there utterly unbothered, not even a crack on its veined gray surface. Short of professional assistance, I suspect it will continue, whispering prayers to its god that no human tool can divulge. I sometimes catch myself wondering about the shape and hue of those prayers. Are they translucent white like his bedfellows’? Does he hold the green tinge of nickel or chromium? The blue of titanium? The dusky pink of manganese? Recently I saw a video of someone guiding a lump of rock past a circular saw. The lump split to reveal black calcite, one of the rarest of all geodes, dark as outer space but flashing with reflected light. Its spangled blackness made this tiny pocket of rock seem infinite, a portal to worlds never imagined. I wonder if we kept our secrets, planned glittering breaths in our days that we would repeat to no one—I will walk down the creek behind my house and tell no one, I will walk out into a particular field south of town and tell no one, I will paint the colors of my sorrows and tell no one—if those galaxies would open within us again, a gently turning inner universe where the mind could wander free.

A couple reading recommendations . . .

If you want beautiful writing about America’s last true wilderness, and astute character sketches of fascinating humans, Coming into the Country by John McPhee is lovely account of his time traveling through Alaska, as well as a smart analysis of the trials the state faced as it tried to balance its responsibilities to conserve its natural spaces, honor its indigenous people, and reap the economic benefits of oil drilling.

If you want an exploration of how to behave morally when the media confronts us with images of suffering around the globe, Regarding the Pain of Others by Susan Sontag is a short, quick read that explains the dissonance so many of us feel every day.

If you want gut-wrenching poetry about how hard it is to be human, Meadowlands by Louise Glück takes the plot of the Odyssey (which I’ve never read) as her starting point. But it doesn’t end there. Instead she uses the basic story to explore the psychological complexities of human relationships.

A beautiful, moving, thoughtful essay! Well and wonderfully done!!

( And I cannot help but wonder: do the two world-lines of the metaverse -- one in which that geode is opened, and the other in which it maintains its secrets forever -- differ in some meaningful fashion? Are there universes where, when some things remain forever beyond the grasp of outsiders, the future is actually better? <sigh> )

This is so great. I was mesmerized.

“Many trees are falling in our collective forests, and we must make sure someone hears ours.” Absolutely floored me.