Split Vision

On love, martial arts, and M. C. Escher

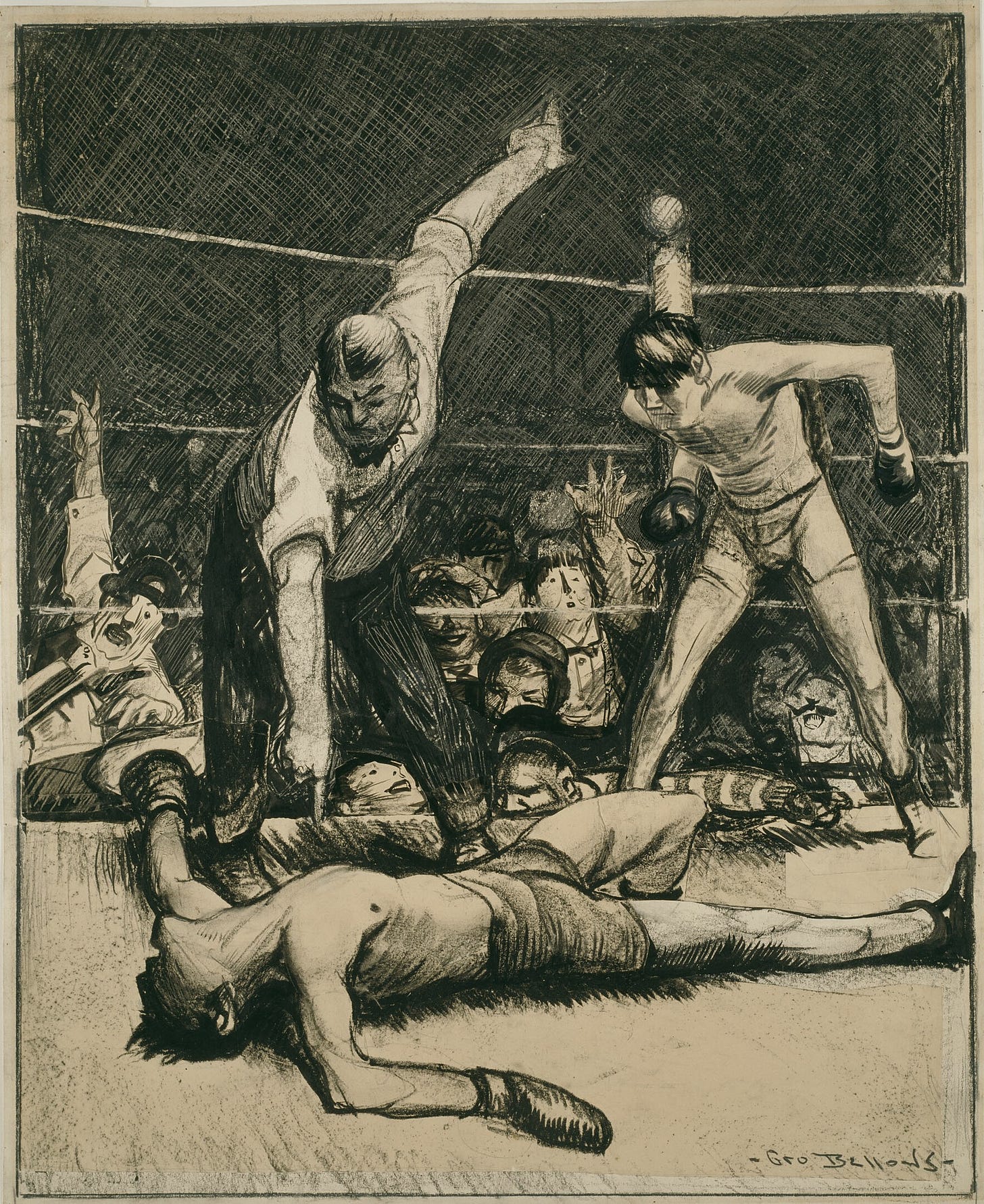

Had you asked me six years ago if would I ever find myself sitting at the local Buffalo Wild Wings, my fingers sticky with Nashville hot sauce, my shoulders clenched as I watched one man pound another and in the UFC octagon, the cornered man bloody from a gash over one eye, his forearms lifted in vain defense while his attacker pummeled his ribs, landing blow after blow until the beaten man stepped forward and hit back hard, knocking his assailant to the mat in one fluid motion as the entire Buffalo Wild Wings, including me, screamed in ecstatic, unadulterated pleasure—I would have said no.

Six years ago, I would have watched uncomfortably, and thought about Roman gladiators, the long term effects of concussions on football players, and humans’ perennial hunger for the spectacle of violence. I would have felt uneasy with so many men yelling all around me, and vaguely compelled to walk up to each of them and explain that Tyler Durden is not the hero in Fight Club. I would have sipped my beer archly, wanting to perform separateness from the crowd, signaling to these men that under no circumstances should any of them come talk to me.

Then I married one of them.

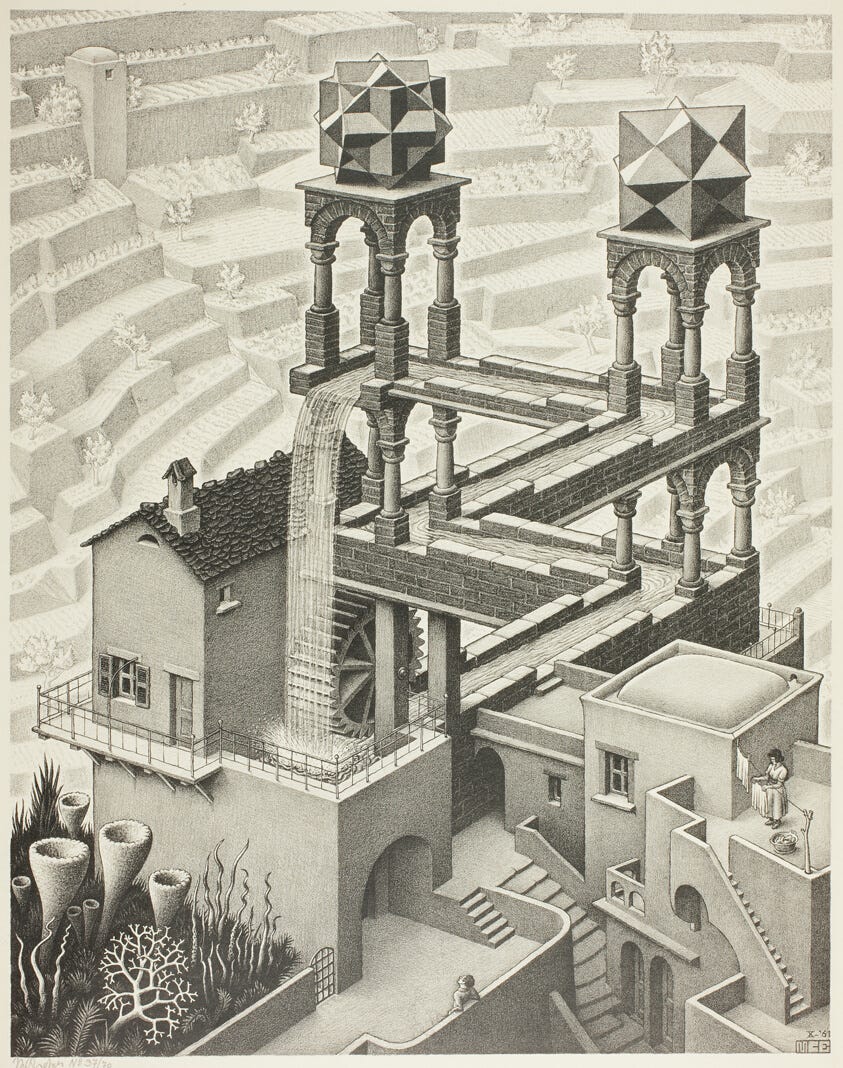

The strange magic of such a transformation, from me then to me now, has something to do with M. C. Escher, the Dutch artist famous for his surreal, perspective-bending images. Take for example his 1961 lithograph Waterfall.

This image disorients us with its impossible geometry. The receding zigzags of the aqueduct make it look like we are standing slightly above the scene looking down as the water flows back away from us into the third dimension of the image. But the stone sides of the aqueduct step downward continuously, as if it were sloping lower and lower toward the earth. Then the vertical columns supporting the aqueduct make it seem like the water is somehow flowing upward to tumble over the edge of the waterfall. The entire image moves in a continuous, illogical spiral, one that constantly destabilizes the perspective of the viewer. What are we looking at? Where are we standing in relation to what we are looking at? Everything shifts.

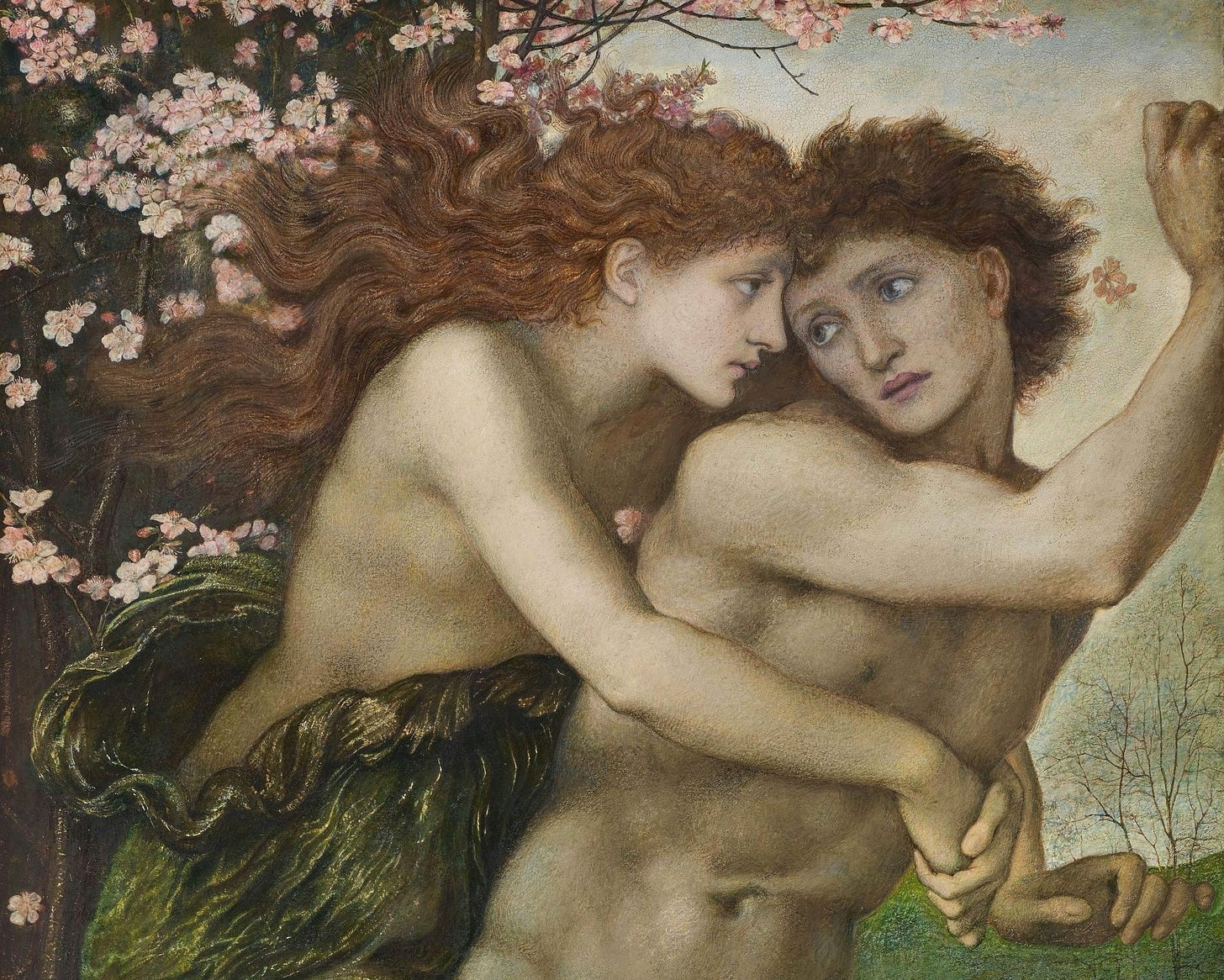

The poet and classicist Anne Carson argued that romantic desire works the same way. For as long as people have been writing love poetry, she argues, they have noted the ways desire creates conflicting thoughts and feelings in us:

I hate and I love. Why? You might ask? I don't know. But I feel it happening and I hurt. - Catallus When I look at Diophantos, new shoot among the young men, I can neither flee nor stay. - Anakreon I know to follow while I flee my fire I freeze when present; when absent, hot is my desire. - Petrarch

Erotic desire, the poets know well, is a longing for what one does not possess, a longing that is pleasure and pain at once. As soon as one possesses their beloved—consummates the match and closes the distance—longing transforms into satisfaction, happiness, bliss. You’d think that’s what we’d want, Carson says.

But we don’t, at least, not always. Whole literary and cinematic genres—the romance novel, the romcom, the love poem, the comedic play—hold the space of desire open for as long as possible, letting us savor its pleasure-pain, its bittersweetness. Many of us have experienced the dull ache of not having crush toward which we can direct our desire. And most of us probably know someone who likes the pursuit of the beloved more than the attainment, likes being love sick. I know I have been that person.

My husband and I danced around each other for years. There he was, leaning on my office door when we were both graduate students, his smile speaking both confidence and self-deprecation, both charm and irony. I hated it. I gave him the iciest stare I could manage and answered his questions in monosyllables. He would try again, every eight months or so, respecting my implied “not a chance, dude” but subtly reminding me the door was open if I changed my mind.

Then we both got hired in the same university department and found ourselves standing by the boxed wine at an office Christmas party, talking about literature and American politics, ethics and aesthetics. Something inside me shifted. He had a brain under that Labrador smile, a good one. And he was charming, despite the fact that he knew it. His green eyes were very, very pretty.

But I was seeing someone, and had been for years, not someone I could throw away lightly. So my one-day-husband and I stayed caught in that erotic space: smiling at each other in the hallways, talking about books before faculty meetings. I tried to keep my distance. Then my relationship exploded under the weight of other circumstances, and the flirtation began in earnest.

Such a longing for love, rolling itself up under my heart, poured down much mist over my eyes, filching out of my chest the soft lungs - Archilochos

We like the disorientation of desire, Carson says, because it holds us in a space where everything is possible. In these moments of longing, the beloved becomes the world to us, becomes everything. And because they are everything, attaining them could make us everything too. Caught in the grip of eros, we brush up against infinity, against the possibility of becoming more, so much more, than our discrete, limited, mortal selves.

He seems to me equal to gods that man who opposite you sits and listens close to your sweet speaking and lovely laughing--oh it puts the heart in my chest on wings. - Sappho

Desire makes us believe we could become something we never thought possible. Anyone who has counseled a lovesick friend knows this. Maybe she’ll marry him! Or maybe she’ll run away to Bali tomorrow. Or maybe she’ll quit her job and move to the wilds of Alaska. Or no, maybe she will marry him.

Maybe, as in an Escher print, water can flow up and down and away from us all at once. Maybe I, feminist grad student that I was, could love UFC.

By destabilizing what is possible and impossible, by throwing all the truths we take for granted out the window, eros makes us see the world through new eyes. Elements of our personality that seemed permanent—me archly sipping a beer in Buffalo Wild Wings—dissolve. After all, as Carson points out, the Ancient Greek’s favorite metaphor for love was melting.

I am like wax of sacred bees like wax as the heat bites in: I melt whenever I look at the fresh limbs of boys. - Pindar

In a sense, the disorientation of desire hot wires our powers of empathy. When the heat of Eros makes everything fluid, when we are desperate to orient ourselves towards our beloved, we find ourselves saying, doing, believing things we would never have thought possible.

So now I sit in Buffalo Wild Wings beside the man who is my husband.

“Jiri has the reach on Jamahal,” I say as the fighters circle each other. “But Jamahal might have more power.”

“Yeah,” he answers. “A lot is going to depend on whether they end up wrestling on the ground or whether they stay on their feet.”

“For sure.” We order another round of drinks.

I understand why he loves this sport. There’s a simplicity to it—no head butts, no eye gouging, no punching below the belt. There’s an elegance as well—two human bodies negotiating strength and weakness, skill and error. It’s a reprieve from the modern world where nothing is simple, where the better fighter often loses, where we find ourselves in fights we didn’t choose. Instead, in the octagon on a Saturday night, two humans willingly submit to one of the oldest, most straightforward contests we know. Who is stronger? Let’s find out. I watch. I melt.

Book recommendations!

If you want a beautifully lyric, intellectually insightful, and profoundly evocative book on the experience of romantic love, read Anne Carson’s Eros: the Bittersweet. Carson is both a poet and classicist by training. In this book she combines analysis of ancient Greek poetry with discussions of art with historical reflections on how the invention of the alphabet changed how humans think about, experience, and relate to each other. It is stunning. I don’t know if this is my favorite book of all time, but it’s definitely in the top five.

If you want a book exploring the ecstatic experience of a UFC fight, read Thrown by Kerry Howley. The book tells the story of a young philosophy graduate student who, in the midst of dissertation writing and personal doldrums, falls in with a group of young martial artists. The book is engaging, fascinating, and delightfully weird. It goes down so easy (I think I finished it in three days). It’s worth noting that the book flirts between fiction and nonfiction. The young men are real people whom the author spent considerable time with during her own graduate school days. But the narrator is fictional. It’s also worth noting that, after the book’s release, several of the young men felt betrayed and misrepresented. I recommend it as an interesting read, but a complicated one.

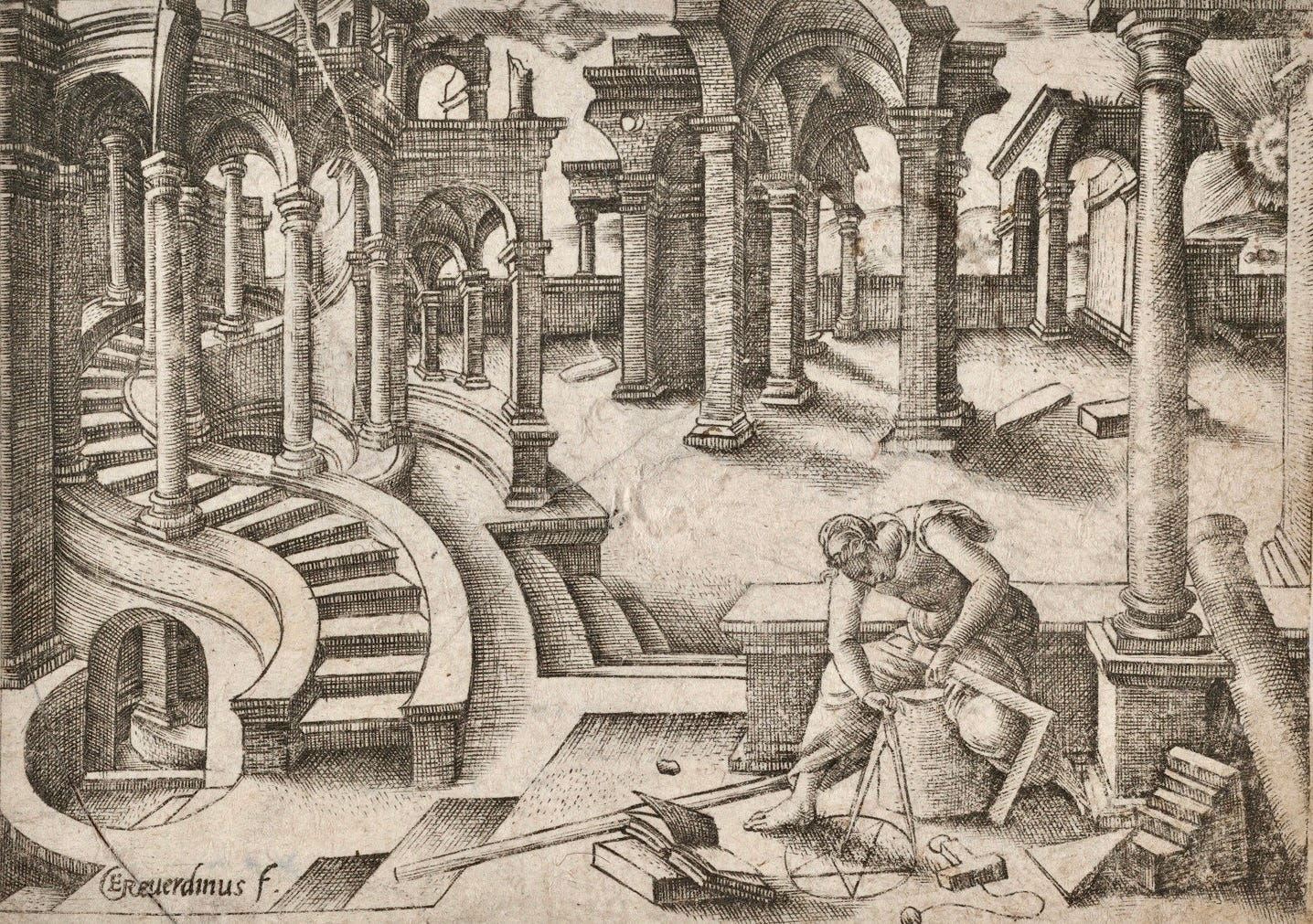

Monument Valley is not a book but a delight. This little phone game uses the playful, Escher-like illusions to create puzzles that are haunting, evocative, and visually stunning. The third installment of the game came out a couple months ago, and I played the entire thing in one enraptured sitting (then promptly went back and played 1 and 2). This is digital media as art, proof that our phones don’t have to pound us with diatribes and advertisements. When used by artists, they can also create silence, questioning, and joy.