The world clamors for my feelings. A woman jogging under warm, early sun tells me about her hardships, her loss, her feeling that she is unwanted and unloved. In her memories a man screams at her as she cowers against a wall. Rain drips down a dark window as she cries into one hand. But in the present she sails into the blazing sun on long strides and a sinuous stretch of asphalt bearing her forever up, and up, and up. All to sell me tennis shoes.

Or a newspaper headline documenting forty-thousand dead above a photograph of a young boy straining over rubble. Tears and blood are on his face. Who knows what he’s lost beneath. I need to hear this news from the world, as surely as I also know that the headline, the photograph, the first lines of the article detailing destruction, are designed to pull my thumb toward the link, toward the profit-making algorithm. I know it’s a ploy.

I know also that I’m being unfair. In a capitalist society all human endeavors—even the best, most earnest, most well-intentioned ones, including these words I write now—are inevitably caught up with money, with buying and selling. So far we haven’t found a better way. Still I hate it. I hate the way these bids for cash take advantage of my tenderness, my desire to be open, present, human. I feel all those images and words, all terrible statistics and building melodic lines hurtling at me from distant sources, aimed at my softer spots, and wonder if it isn’t better to brick in the windows of my heart. Better that, I tell myself, than leaving my deepest places open to such blatant machinations.

And then, a week ago, I saw this painting as I walked the soft-lit rooms of a gallery in Spain.

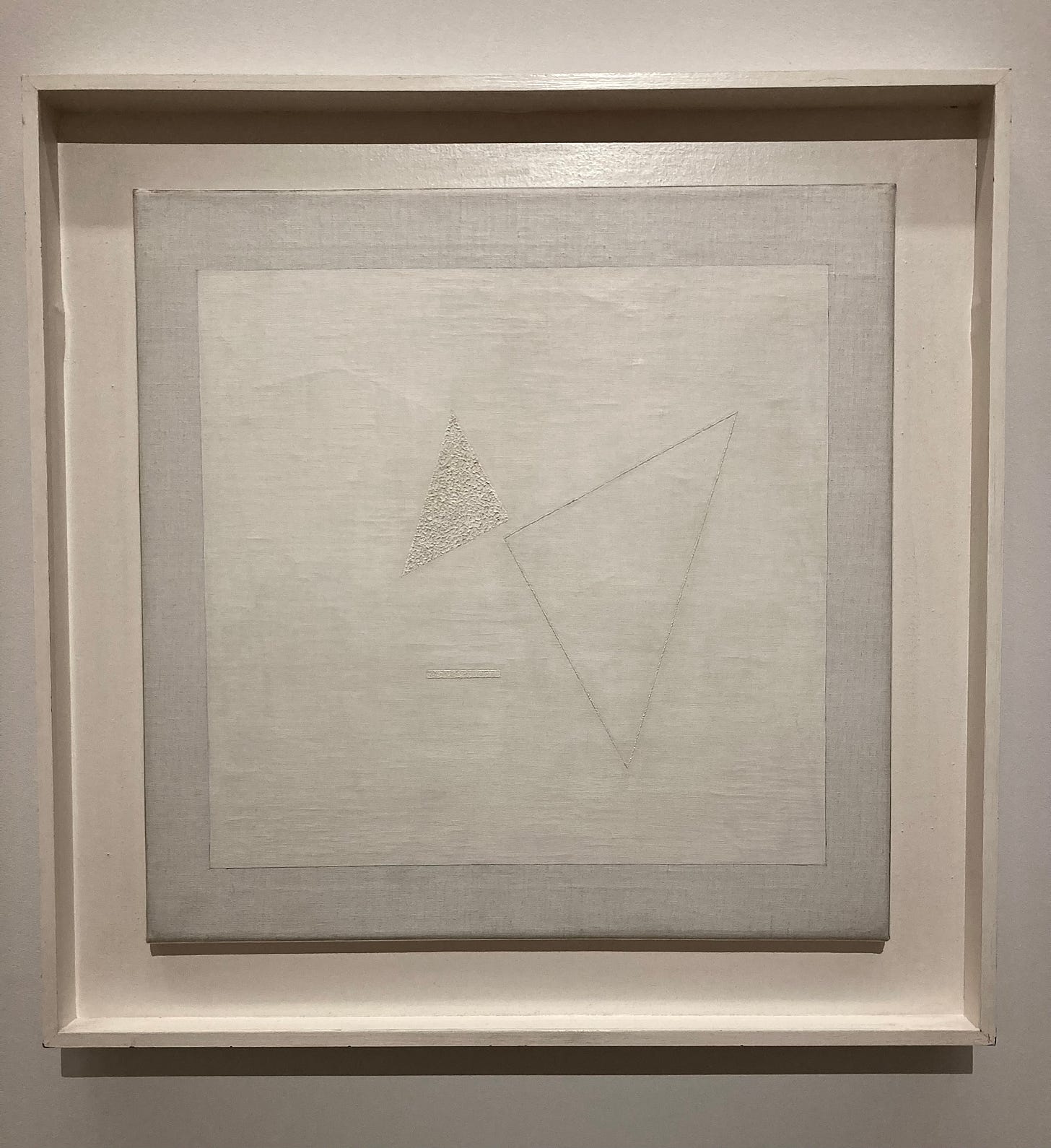

Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart created these gentle little triangles at a particularly difficult moment. Born in eastern Germany at the very end of the nineteenth century, he came into his artistic power just as the Nazi party was gaining traction. His art was not to their tastes—experimental, abstract, emasculated as they saw it. It did not espouse the “blood and soil” values of militarism and patriotism they held dear. Art such as this, they thought, could only be produced by someone so coddled by modern society, so weak and feeble that they had lost the self control to produce more traditionally representational work. Those who created paintings such as his were deformed, and potentially criminal.

So in 1936 Vordemberge-Gildewart fled west to Berlin where the party had not yet gained so strong a foothold, and as he continued to work and showcase his paintings, the Nazis denounced him as unGerman, including several of his canvases in their exhibition of “degenerate art.” They confiscated the paintings they included. It was around that time that he completed Composition No. 104 White on White.

As I stood in the gallery staring at this simple canvas, I felt something inside me disarm. How delicate that pale, pale square inside its frame, not the stark white of snow or freshly bleached cotton, not a color that implied perfection, absolute purity, but rather a grayish, human white. Like an eggshell. Like the whites of my eyes. Imperfect, mottled, immanently breakable.

And those two little triangles, what were they doing all alone there in that empty plane? Almost touching. Tentative, it seemed to me. Uncertain of each other. Wanting to touch but afraid to, afraid of what might happen next.

I was surprised by my reaction. I’ve always been open to abstract art, but it’s rarely moved me the way other art has. Usually I prefer the plays of light and shadow in the impressionists and post impressionists—the evocative, swirling colors of Monet and Van Gogh, the soft leafy, greenery of Renoir and Matisse. Even among abstract painters, I usually gravitate towards artists with more movement and depth, the stained glass light of Gino Severini or the exuberant swirls of Kazuo Shiraga. By contrast this pale painting, with its two little triangles and spare, narrow rectangle (look close) seemed far beyond the usual margins of my taste.

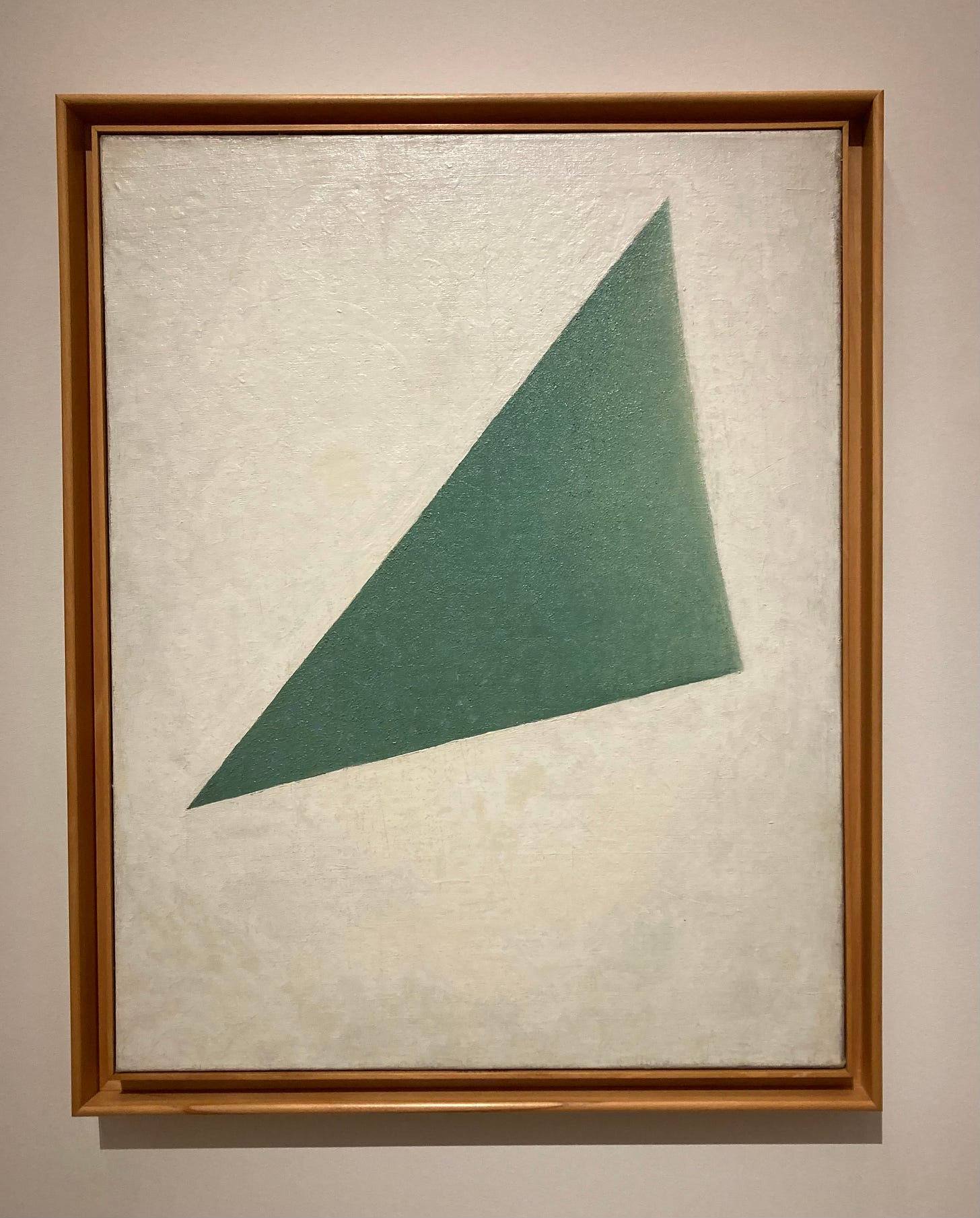

But as I moved from Vordemberge-Gildewart’s canvas along the gallery wall, another bit of geometry leapt toward me, this time in green.

That same pale, mottled background, like stratus clouds or ash. And this time a green triangle, dark and crisp in the lower left but on its long right side fading, lightening, blurring as if lifted by light into somewhere else.

The world that clamors after my feelings, tries to exploit every emotion, every empathetic impulse, turn it to profit, seemed to fall away. Here, this painting beckoned, here I’m putting down all the easy tools. All the tools that have been turned against you. See I’m putting down story, tragedy, character, setting. See I’m putting down color and motion. It’s okay. It’s okay. I am not like those others. Just sit here quietly with these little triangles I’ve made for you. See if they can’t make your heart flutter awake with something true.

Like an injured dog who, coming across a man in the woods, sees him put down his hunting rifle and crouch to the snow, a hesitant part of my heart sniffed the air and took a cautious step forward.

As violence stoked and strengthened in Germany, Vordemberge-Gildewart fled to Amsterdam where he lived in hiding through the war and the Nazi occupation. He continued to paint. He tried to create paintings that were an antithesis to the chaos and confusion around him, recalled friend and sculptor Hans Arp, a haven amid all the art promoting soil and blood, amid all the very real blood that followed.

See, Friedrich’s triangles whispered to me. Even when we put down the melodrama and rousing music, even when we pair ourselves down to the barest elements, the simplest forms, still your inner well of feeling rouses. Still some kinship in you reaches out. Stripped down to nothing, nothing more than tender geometry, your soul stirs, still soft, still human, after all.

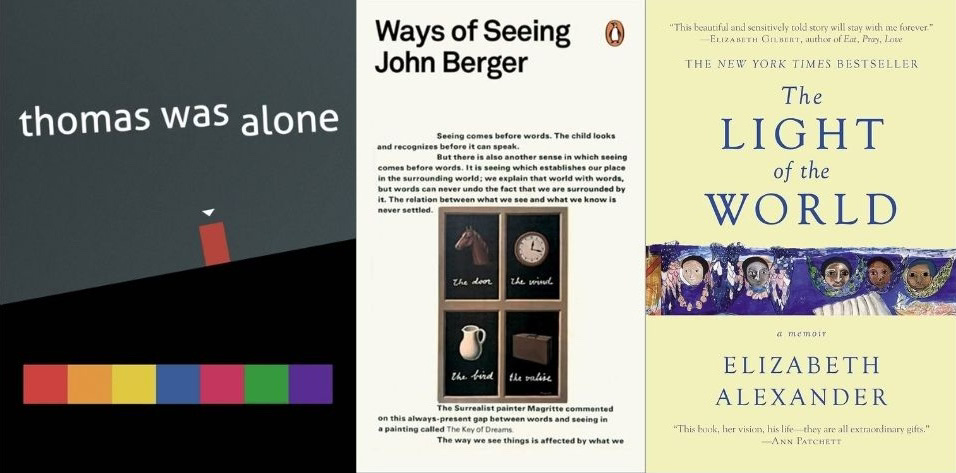

A couple recommendations . . .

If you want some tender geometry in your days, I recommend this delightful little video game Thomas Was Alone. I have played less than twenty hours of video games in my entire life, but this gem thoroughly charmed me. All the characters are little rectangles who find themselves in a series of puzzles and mazes. Somehow the game draws incredible poignancy, dare I say philosophy, out of such a simple premise. Bonus, you can usually get it for less than $5 on Steam.

If you want to read more about art and the ways advertising is stealing our collective peace, try Ways of Seeing by John Berger. A prize winning novelist, Berger started as an art critic and his gift with language shines in this slim volume (which you can also read for free here, or watch as a documentary on Youtube, if you so choose). The final chapter details how image-based advertising causes us to always compare ourselves to an imaginary version of ourselves we could be if only we bought the product. As Berger puts it, “the publicity image steals [the viewer’s] love of herself as she is, and offers it back to her for the price of the product.”

If you want a big-hearted, generous book about grief, cooking, art, and love, read Elizabeth Alexander’s Light of the World. After the sudden death of her husband, Alexander cooked and wrote to reconnect with her children and wade through her loss. Despite its subject matter (because of it?) the book has an incredible warmth, perfect for a chilly day or chilly spirit.